The Atlantic’s Elizabeth Bruenig on her “hypothetical,” heavily reported measles essay

“The birthday-party invitation said ‘siblings welcome,’ which means you can bring your 11-month-old son while your husband is out of town,” Elizabeth Bruenig’s piece begins.

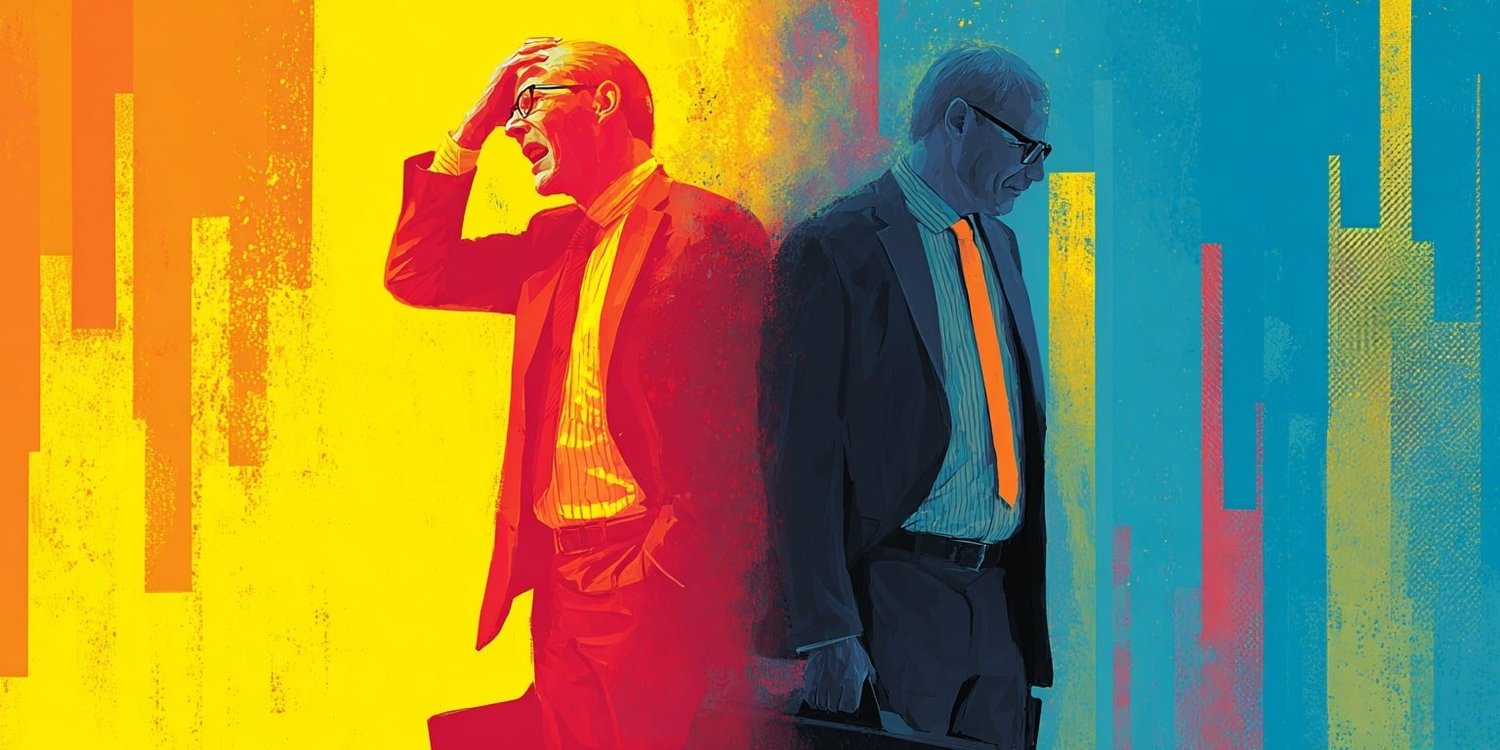

“This is how a child dies of measles” was published by The Atlantic on Thursday afternoon and is currently the most popular story on site. It’s written in the second person, from the point of view of a woman whose two unvaccinated children get measles — with ultimately horrific long-term consequences for her son.

The story is filled with details of modern everyday life (“You plant her on the couch with a blanket and put Bluey on the TV while she drifts in and out of sleep,” “While the kids are napping, you tap a list of your daughter’s symptoms into Google and find a slew of diseases that more or less match up”), juxtaposed with descriptions of a disease that was considered eliminated in the U.S. in the year 2000 — but reached its highest levels in three decades in 2025. (“Her cough wracks her whole body, rounding her delicate bird shoulders. She does not sleep well. And as you lift up her pajama top to check her rash one morning, you see that her breathing is labored, shadows pooling between her ribs when she sucks in air.”) There have been five measles outbreaks in the U.S. so far in 2026, according to the CDC.

When I initially read Bruenig’s story, I was stunned: An Atlantic staff writer’s unvaccinated child had died of measles in the 2020s, and now she was writing about it? At the end of Bruenig’s piece, though, there’s an editor’s note: “This story is based on extensive reporting and interviews with physicians, including those who have cared directly for patients with measles.” That was the point when I sent a gift link to my mom group: “as far as I can tell this piece is fiction. What do we think about this choice? I am very conflicted!!!” My conflict stemmed from my concern that, though the piece was heavily researched, it was not a true story. I wondered if the key people whose minds might be changed by it — people who don’t vaccinate their kids — would brush it off as fiction, or fake.

Some Atlantic readers seem to share my sense of conflict — or missed the editor’s note and thought it was true. “Thank you to this mom for the incredible generosity of sharing this story — nothing could be more tragic. I’m so sorry,” one commenter wrote.

Another reader commented: “Beautiful, powerful writing! This is not the reporter’s personal story, correct? Is it one family’s true story or a composite based on her reporting? I find it very compelling and potentially persuasive to families who question vaccines. I would love to know more about how the piece came together.”

I wanted to know that too, so I asked Bruenig some questions via email. (By the way, if you like learning about how reported stories come together in general, you should check out our sister publication Nieman Storyboard. And if you want to see another time that Nieman Lab asked a reporter questions like this, check out my colleague Sarah’s interview with Rachel Aviv or Neel’s interview with Sarah Zhang.) Our conversation, very lightly edited for clarity (and I added the links to statistics cited) is below. The piece is here.

Writing in the second person made sense to me because it’s a hypothetical addressed to parents weighing these decisions or facing outbreaks in their communities. I write nonfiction either in the first person or third, so this felt like a way to signal that this is a different kind of story. On the other hand, writing in the second person always feels a little bit goofy.

We included an editor’s note to remove any possibility of confusion. And yes, it does make sense to me to describe it as a story about ideas.

I also thought about the conversations I’ve seen play out in moms groups, both in person and on social media, which informed my ideas about where this mom may have encountered anti-vax views. So many parenting decisions are based on different forms of anxiety, in my experience, so I feel a lot of solidarity with parents striving to do what is best for their kids, even if I find their conclusions questionable. I didn’t want this mom to be aggressively confident or evangelical in her vaccine skepticism, because I didn’t want her to be a caricature. I did not want the piece to come off as mocking or shaming. I didn’t want to judge her, and I didn’t want to imply that she does not love her children. I wanted her to feel human.

How were you thinking about this? I imagine you thought about it a lot. As a very pro-vaccinating mom, I am so split on this. On the one hand it’s a new way to reach people who just wouldn’t read pro-vaccination content otherwise. On the other hand, did you worry they’ll blow it off or think it is sensationalized?

Because the measles virus in the United States has been suppressed for so long by vaccinations, it is easy to forget that this is a serious illness. I was surprised by several things I learned in the course of this reporting. (I had no idea, for instance, that measles suppresses the immune system, providing ideal conditions for secondary infections.)

But my job is to report the truth about the world — and I use all kinds of literary, and narrative devices to do that. I do it because telling the truth is important in its own right, whether or not anyone finds it persuasive.

I hope there’s a sliver of a chance this reaches people who are really weighing these issues and making decisions about their children’s health in real time, or people who have friends and family weighing whether to vaccinate, or people living in communities currently managing outbreaks. I’m not very confident that it could persuade people who have very firm anti-vax convictions — as you point out, it seems pretty likely they would just blow it off. That’s always a risk anytime you write with a hint of persuasion in mind. But if the story makes even a little bit of a difference in even one person’s decision making where it comes to vaccines, then it was a success.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0