In the video game News Tower, as in real life, running a newspaper isn’t easy

My newspaper had a bat problem, in that bats — of the baseball variety — were the preferred weapon of the mobsters intimidating my employees and smashing up my office.

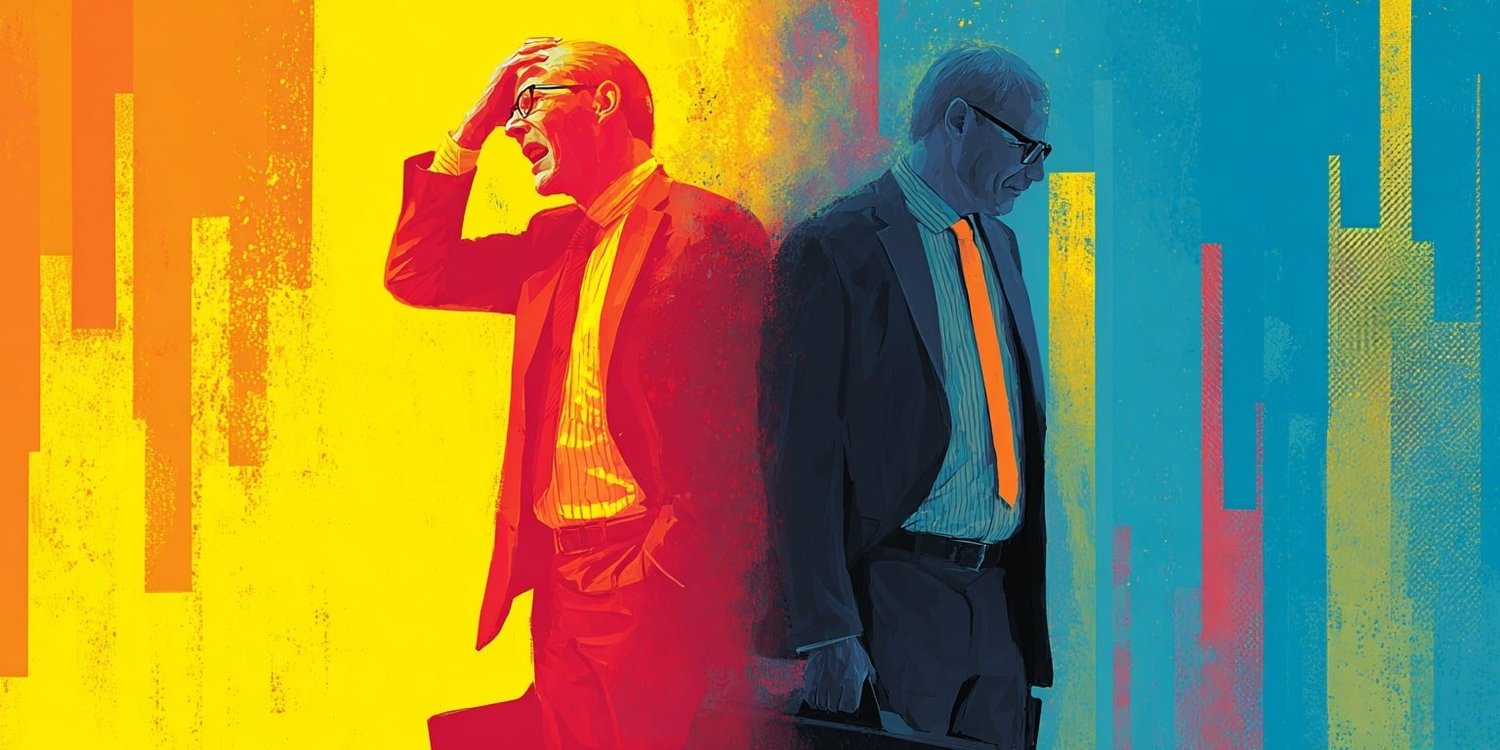

These are the kinds of problems you deal with in News Tower, a management-simulation game for PC and Mac from Dutch developer Sparrow Night that launched last November and has players stepping into the shoes of a New York City newspaper publisher in the 1930s. (Andrew recommended News Tower in our gift guide last year.)

Management sims are all about decisions; in News Tower, my first decision was the name of my newspaper. This being Nieman Lab, I decided to call my newspaper The Experiment. Some things about the game are all too familiar to anyone who’s paid any attention to the state of journalism lately. When you first start the game, the paper is struggling:

Evergreen.

You have a few options for getting out of the hole. You can take out a loan, for instance. Or you can turn to the same mobsters who smashed up your office for help, just as your father and uncle (who cofounded the paper) did. But to get their help, you have to print stories that are friendly to them — or avoid stories that might make them look bad, like coverage of a gruesome murder.

The news business of the 1930s, it turns out, is the business of influence, and everyone — the mafia, the mayor, wealthy socialites, the military — had thoughts on what I should and shouldn’t print. Success, or at the very least survival, requires balancing those interests, choosing which factions to cozy up to and whose wrath to risk in return. The more favors you perform for a faction, the better the rewards: cozying up to the military, for example, would reduce the cost of the steel required to expand my eponymous tower ever-upwards.

At first, I tried to avoid the factions entirely, which I quickly found was a losing strategy. Instead, I only accepted missions that, if not living up to the journalistic standards of 2026, at least didn’t entirely betray my ideals. I wouldn’t, for example, help the mayor sweep a scandal under the rug, but I also generally avoided gaining standing with his enemies in the mafia because doing so would weaken my employees’ union — something that I, a member of multiple journalism unions over the years, couldn’t abide.

The Experiment prints on Sundays — no daily news cycle here — and I’d spend the intervening days sending my reporters around the country (and occasionally across the pond to Europe) to chase down scoops that would help me push in on the territory of competing newspapers. Many of the headlines in the game are drawn from, or inspired by, real-life news from the era; my reporters brought back stories about Al Capone being sent to prison, the looming economic crisis, and the premiere of the first-ever animated film.

Also evergreen.

I also had to balance all the needs of my employees. Reporters and editors were only a part of my staff: I also employed typesetters and assemblers who quite literally put my paper together each week, telegraph operators who kept a finger on the pulse of the world, lawyers who dealt with lawsuits, and janitors, security guards, assorted maintenance workers who kept the building running. Each of them had their own needs, and making sure I paid attention to all of them was essential to getting my paper filled with stories and out in time each week.

As my paper grew, the perception of my paper became more and more important. In a slight twist from the left-right politics of the real world,I could choose to chase stories that would make readers think of it as informational (the game’s “left”), sensational (“right”), or a moderate middle. A story about a new scientific discovery for example, nudged the perception left, while a story about a spate of murders moved it to the right. This became increasingly important as I inched into the territory of my competitors, each of which had their own editorial bent; the New York of News Tower has no room for a robust information ecosystem with multiple papers, and I had to swing my paper’s editorial slant wildly to steal more and more subscribers away — which, as anyone in 2026 might be able to tell you, is perhaps not the most well-informed strategy.

What is this, a Christmas tree farm?

I played News Tower for about ten hours, and I can’t wait to go back; I could tell I was only scratching the surface. Playing it was surprisingly cathartic — a reminder that good journalism, while always hard to produce, was at one point rewarded richly — and sobering. It even, slightly, made me feel a little bit sympathetic toward the people in charge of The Washington Post. But only a little: no matter what the mayor threatened, I still printed stories about his scandals.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0