In Medill’s latest State of Local News report, a “festering, 20-year-old problem” looms larger than ever

Built into Nieman Lab’s mission is a commitment to be “fundamentally optimistic.” It is challenging to read Medill’s 2025 State of Local News Report and hold onto that optimism.

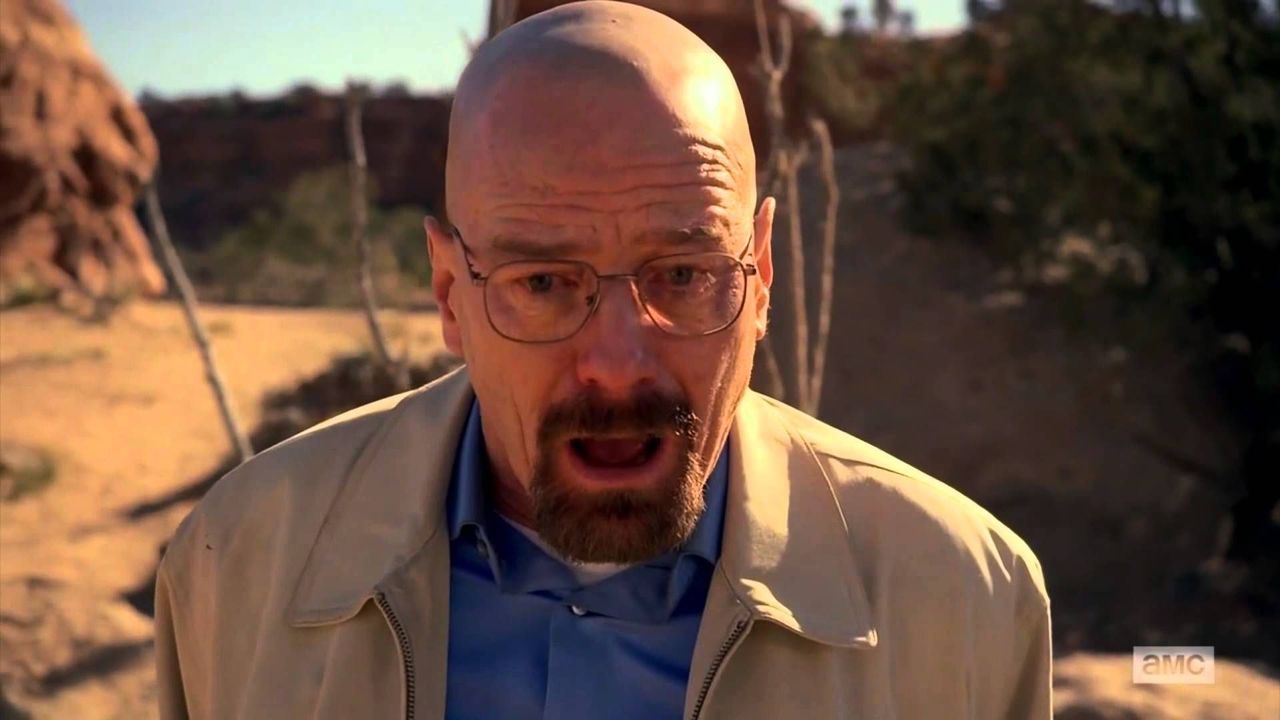

While there are a dozen bright spots rightly celebrated in the report’s recurring feature — from Ken Doctor’s expansion of Lookout Local, to the Hearst-owned Houston Chronicle, to the nonprofit network Deep South Today — those bright spots are pinpricks against a backdrop of cumulative losses to readership, jobs, and newspapers documented in this report. As Rebuild Local News’ Steven Waldman put it, “We’re losing the race against time.”

The report, now in its 10th year, draws on two decades of data, starting with 2005. It tracks 8,000 American local news outlets, including more than 5,400 newspapers, almost 700 standalone digital sites, more than 840 network-operated digital sites, more than 650 ethnic and foreign language organizations, and more than 340 public broadcasters.

Of all the declines quantified, to me, digital readership stood out. While declines to print readership are almost a foregone conclusion, “digital traffic to local news sites is experiencing a cratering similar to that of print,” State of Local News Project director Zach Metzger writes in the report.

The form of media that punches above its weight in rural areas is public broadcasting. “Although two-thirds of radio stations emanate from urban locations,” the report states, “the remainder are spread throughout the country, bringing local news to many rural regions that are otherwise underserved by local sources.”This year’s Medill report dives deeper into the state of public broadcasting than its predecessors, with a database tracking “nearly 300 radio stations and more than 100 public television stations that originate local reporting content within their programming” as well as “hundreds of repeater and affiliate signals that broaden the geographic reach of these stations.” That data shows just how important a role the medium plays in reaching many areas otherwise classified as news deserts:

“In nine counties — six in Alaska, one in Idaho, one in New Mexico and one in South Dakota — a public broadcasting station is the sole source of local news coverage,” the report states. “In 47 other counties, public media is one of only two sources, with the other typically being a weekly newspaper.”

“One of the key advantages of public broadcasting that makes it a potential remedy to news deserts is that the signals from many stations reach into areas with limited access to other forms of news,” Metzger writes in the report. When Medill researchers conducted an analysis of the signal contours for the public radio stations in their database, they found “the primary stations reach into 46% of news desert counties and 53% of counties with only one news source,” the report states. “When repeaters are included, this reach jumps dramatically, with signals extending into 82% of news deserts and 90% of single-source counties.”

This context helps illustrate the stakes of the federal funding cuts to public broadcasting. The rescission of federal funds “posed a sudden and significant threat to stations across the country,” the report states. The hardest-hit stations tend to be in poorer, rural areas:

In a review of station finances from 2023 and 2024, we found that roughly two-thirds of stations receive more than 10% of their funding from government sources through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. In about 10% of stations, that support counts for more than 40% of funding, putting these stations at elevated risk of having to drastically scale back operations or shut down entirely. The stations with the highest dependencies tend to be those located in poorer, more rural areas. Of the 24 counties with stations that receive more than 40% of their funding from federal sources, half are classified as very rural. These stations face a dual challenge: A large percentage of their funding has vanished, and they cannot make up the deficit through audience or local business donations, as stations in more urban areas might be able to do.At the same time, the report notes that the disappearances of newspapers “are especially pronounced in the suburbs of large cities, where hundreds of papers have merged together.”

The crisis of local news is often characterized as a rural problem, but in terms of magnitude, the disappearance of local newspapers has most starkly impacted urban and suburban areas. Of the 3,500 newspapers that have vanished since 2005, almost 70% disappeared from counties categorized as predominantly urban. A quarter of newspaper losses have occurred in just 10 metropolitan areas, with New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia and Minneapolis the five cities most affected. Almost a third of U.S. cities have lost more than half of their newspapers. Some have lost significantly more: Milwaukee, for example, has lost 80% of its newspapers over the past two decades, as has Rochester, New York. Columbus, Ohio, has lost 74%, with more than 45 papers vanishing.In part, these urban losses have been greater because these areas had the most to lose. But they also speak to how newspapers have disappeared. Suburban newspapers proved particularly vulnerable to the mass consolidations carried out by large chains.

Two other high-level indicators of decline across the country from the report:

- News deserts up: Since 2005, “almost 40% of all local U.S. newspapers have vanished.” Medill documents 213 U.S. counties “without any local news source, up from 206 last year” — almost 80% of these are in counties the USDA classifies as predominantly rural.

- In the past year, 136 newspapers disappeared due to closures or mergers. In a difference from some previous years, most of the newspapers lost were “smaller, independent chains and outlets,” not the papers owned by large chains.

- Meanwhile, “in another 1,524 counties, there is only one news source remaining, typically a weekly newspaper. Taken together, in these counties some 50 million Americans live with limited or no access to local news.” For the people living in these counties — which tend to be poorer and less well educated, with underdeveloped technological infrastructure — “lack of access to local news is one of many interconnected inequalities.”

- Jobs down: “Since 2005, more than 270,000 newspaper jobs have vanished, a loss of more than 75%.” Newspapers remain the single largest category of employment for journalism jobs, though it accounts for less than a third of the nearly 42,000 journalists in the U.S.; digital media and broadcast reporting each account for about a quarter of employment.

All told, the journalist occupation declined by a little more than 7% from 2023 to 2024, almost identical to the decrease among newspaper publishers. Over that same time frame, journalist jobs fared worse than 85% of all occupations tracked by the BLS.

As for the bright spots, a few things the dozen highlighted news outlets have in common:

- Eleven of the 12 are locally controlled (the exception is the Hearst-owned Houston Chronicle).

- Both for-profits and nonprofits are pursuing philanthropic support.

- “Partnerships and collaborations — whether with other news outlets, local businesses or education institutions — expand audience reach and strengthen engagement.”

- “A recurring theme across conversations was the importance of testing initiatives, iterating, incorporating feedback and being willing to fail fast.”

- “With the demise of the print-advertising-based business model, reader revenue is increasingly valued, though there is no consensus view on paywalls vs. memberships and donations.”

- “Whether seeking outside support or shifting internal resources, leaders at all outlets stressed the importance of studying audience consumption habits and potential information gaps to align projects and beats with audience needs.”

For all the data and charts, this report left me thinking about a poem by Franny Choi, “The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On.”

everywhere, the apocalypse rumbled,

the apocalypse remembered, our dear, beloved apocalypse — it drifted

slowly from the trees all around us, so loud we stopped hearing it.The local news apocalypse keeps rumbling, and local news goes on.

Read the full report here (and keep an eye out for forthcoming deeper dives into public broadcasting, local news in Baltimore, family owners of local news outlets, and local news newsletters).

- Dan Kennedy points out that the county-based methodology is imperfect, using our own backyard to demonstrate its oversights: Per Medill’s database, “you’ll see that Massachusetts is a veritable news oasis, with no counties that would qualify as news deserts. But we have just the barest vestiges of county government in Massachusetts. Instead, we have 351 cities and towns, each with its own city council or select board, school committee, police department and the like. Every one of those communities needs accountability journalism. Unfortunately, we are a state where one small town may have a strong local news outlet and another, bordering town has nothing. Medill’s methodology may work for much of the country, but it doesn’t work here.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0